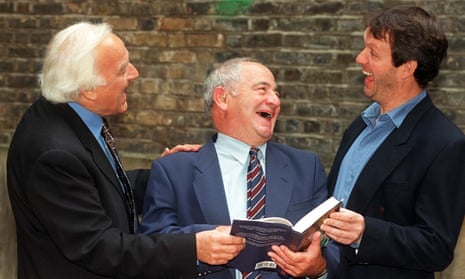

“Game-changer” is a word Colin Dexter, who died this week, would almost certainly have loathed. But it exactly describes what Dexter himself was, via TV’s Inspector Morse. Though it might seem his legacy is limited to a handful of novels, it is actually far larger than that: publishers’ insatiable enthusiasm today for crime fiction, the shelf space bookshops now allocate to it, the number of writers making a living from it.

What he crucially changed was the genre’s relationship with television. Before Inspector Morse’s debut in January 1987, dead crime writers – Conan Doyle, Christie, other golden age authors – were regularly adapted in period dramas with high production values; whereas the tacit assumption was that present-day crime should be tackled in original series, which might be hardboiled like Taggart or easygoing like Bergerac.

ITV’s Inspector Morse gave Dexter’s novels the kind of deluxe treatment hitherto reserved for Poirot, Maigret and Sherlock Holmes’s investigations. Created by Kenny McBain and Anthony Minghella, it mimicked movies in the episodes’ two-hour length. Their eye-bathing Oxford visuals were deftly blended with the music (new by Barrington Pheloung, old from Morse’s beloved operas) and the scripts were written by hot playwrights such as Minghella and Julian Mitchell.

It demonstrated that contemporary crime fiction could be adapted with stunningly good results, if sufficient care and resources were lavished on it, and several other things too. Inspector Morse did wonders for ITV and its makers commercially, attracting the affluent viewers advertisers craved and going on to be exported to 200 countries; it also made the network look classier, and similarly enhanced the image of its originating ITV region, Central - at a time of rivalry between baronies, other broadcasters took note that a detective like Morse could be a kind of standard-bearer for a sizeable chunk of Britain.

Another valuable lesson derivable from Inspector Morse was that contemporary crime-writing could be as malleable as the old variety, even though the author was still around to potentially protest. The series’ creators changed Sergeant Lewis from a Welshman in his 60s to a fresh-faced Geordie, made the dyspeptic detective somewhat less unpleasant and sexist, and gave him a Jaguar (made in Coventry in Central territory) instead of a Lancia; the individual adaptations meddled with the novels’ plots. Yet Dexter gave it all his blessing, as symbolised by his Hitchcockian cameos.

With Sussex-based reworkings of Ruth Rendell’s Inspector Wexford novels debuting later in 1987, the year began a boom time for TV crime adaptations, with every ITV and BBC region wanting its own Morse and TV schedules consequently dominated by provincial sleuths who were mostly grumpy middle-aged men, too. And a boom in British crime-writing followed, with star authors advancing to the top of bestseller charts, and publishers launching crime lists and frantically signing up newcomers in the hope that they would be the next Dexter, Rendell, Ian Rankin or Val McDermid. (In the US, in contrast, only a few of the big names have been adapted for television or cinema, and original TV crime such as CSI has remained dominant.)

Whether through miscasting, penny-pinching, misguided adaptation approaches or the novels simply not being suitable, however, the alter egos of the likes of Rankin and McDermid did not prove to be most durable as telly cops plucked from books proliferated – it was the relatively obscure RD Wingfield (A Touch of Frost) and Caroline Graham (Midsomer Murders) whose detectives went on solving murders for decades. For the award-winning authors regarded as pre-eminent, though, even short-lived TV outings helpfully soldered their names to their protagonists’ in the public mind and singled them out as reliable storytellers.

Thirty years on, the Dexter-inspired ascendancy in detective-novel adaptations looks to be waning: TV’s pendulum has swung back to original creations such as Broadchurch, Line of Duty and “Scandi crime” series. But the Inspector Morse effect can still be seen in the form of publishers’ hunger for psychological thrillers, impelled by a similar hope that screen transformation – Gone Girl, Before I Go to Sleep and The Girl on the Train on film, Apple Tree Yard on the small screen – will multiply book sales spectacularly in the UK and abroad.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion