When Chuck Berry wrote School Day (Ring Ring Goes the Bell), his detailed evocation of a day in the life of an American teenager in the Eisenhower era, he created an anthem for a generation: “As soon as three o’clock rolls around, you finally lay your burden down / Close up your books, get out of your seat / Down the hall and into the street / Up the corner and round the bend / Right to the juke joint you go in.” What he also provided was an education. Young Britons of the postwar era took their 11-plus exams, followed a few years later by their O-levels. In between, a significant number of them studied Chuck Berry.

Also on the informal course were the works of Bo Diddley and Jimmy Reed. The more advanced students made their way to Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson and John Lee Hooker. But among the array of great American rhythm and blues heroes, it was Berry who provided the most stimulating and influential set texts, mainly because it was in his work that the harsh poetry of the blues was softened, streamlined and neon-lit in a way that made it immediately palatable to a young white audience.

To the generation born in Britain around the end of the second world war, his songs opened up a new world. What Little Richard and Elvis Presley suggested in sound, he portrayed in words as well: a world of freedom and pleasure, in which adults no longer set the whole agenda.

It was Berry who presented kids still going to school on a bike or in a trolleybus with the exhilarating details of a battle on the open highway between a Cadillac Coupe de Ville and a V8 Ford, and with lascivious descriptions of girls like the immortal Little Queenie: “There she is again, standing over by the record machine / Looking like a model on the cover of a magazine / She’s too cute to be a minute over 17.” With minds inflamed by such images, we found ourselves looking at our parents’ Morris Minor and our neighbours’ daughter in a quite different light.

Those of us who had never even seen a jukebox heard from his lips what it might be like to drop the coin into the slot and hear something that’s really hot. In a provincial England where Levi jeans and white T-shirts were virtually unobtainable, Berry’s word-pictures were a tantalising glimpse of a better world elsewhere, or at least one soon to come.

Skiffle had been the musical 11-plus. All you needed for a passable mastery was a washboard, a tea-chest bass, some sort of guitar, possibly home-made, and unlimited enthusiasm. And when that became too restricting a form, when you were putting away the washboard and the Lonnie Donegan Fan Club badge, moving on from the works of Lead Belly and Big Bill Broonzy and getting hold of a real electric guitar and a rudimentary drum kit, Chuck Berry was what happened next.

Instead of a music that reflected the experience of hobos riding the rails or convicts on a chain gang in some southern penitentiary, here was the soundtrack to the experience of being a teenager in the postwar years of growing affluence, when society’s rules were being gently tested for what seemed like the first time: “Sweet little 16, she’s got the grownup blues / Tight dresses and lipstick, she’s sporting high-heeled shoes / Oh, but tomorrow morning she’ll have to change her trend / And be sweet 16 and back in class again.” Roll Over Beethoven seemed, if not exactly a call to the barricades, then a harbinger of the end of deference.

Berry’s influence was (and is) everywhere, starting with every note ever played by Keith Richards, who mastered Berry’s distinctive hard-driving riffs – as heard on the introductions to Johnny B Goode, Sweet Little Rock’n’Roller and Promised Land – and fashioned them into his own style. By learning how to play Berry’s signature figures, in their simple but potent thirds and fourths, a young musician acquired free access to the driving momentum of early rock’n’roll. This was a cooler, more modern equivalent of Fats Domino’s or Little Richard’s hammered boogie-woogie eight-to-the-bar piano riffs – cooler and more modern because it was played on an electric guitar, a glittering and still exotic device that, unlike the upright Victorian keyboard instrument residing in your parents’ parlour, clearly belonged amid the glittering of the world of tailfins and jukeboxes.

Richards’ group even made their recording debut with a Berry song, Come On, with its typically wry lyric: “Everything is wrong since me and my baby parted / All day long I’m walking cos I couldn’t get my car started / Laid off from my job and I can’t afford to check it / I wish somebody’d come along and run into it and wreck it …” The group’s singer, Mick Jagger, found just the right tone of youthful petulance.

Naturally, there were young Americans who responded to what Berry was doing. Buddy Holly, the first great white rock’n’roll singer-songwriter, had a posthumous UK hit with his cover of Brown-Eyed Handsome Man. The Beach Boys took Sweet Little Sixteen and turned it into Surfin’ USA. But it was in Britain that the spark turned into a blaze.

In those days, you went to a club to see a Mersey Sound group or an R&B band from the Thames Delta, at a time before any of them got famous, simply hoping to hear one or more of Berry’s songs played live, with those guitar riffs powering out of a Vox. For a while, the Stones practically lived off his work. Carol was on their first album, I’m Talkin’ About You was on Out of Our Heads, and Little Queenie was still in their repertoire when a 1969 show at Madison Square Garden was released as Get Yer Ya-Yas Out. Like many others, they borrowed his radical rearrangements of Bobby Troup’s Route 66 and Don Raye’s Down the Road Apiece.

The Beatles’ second album included Roll Over Beethoven, and the anthemic Rock’n’Roll Music appeared on Beatles for Sale. A few years later, on the White Album, Paul McCartney paid homage to Back in the USA with Back in the USSR. John Lennon, who once said, “If you had to try and give rock’n’roll another name, you might call it Chuck Berry”, modelled a line in Abbey Road’s Come Together – “Here come ol’ flat-top, he come groovin’ up slowly” – on one from Berry’s You Can’t Catch Me.

The rapid-fire complaint of Too Much Monkey Business would inspire Bob Dylan’s game-changing Subterranean Homesick Blues in 1965. Eight years later, Bruce Springsteen borrowed the same template for Blinded by the Light, the first track on his debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ, and thus the song with which he announced himself to the world.

Let It Rock – another anthem – gave its title to that of a magazine founded in London in 1972 by the late Charlie Gillett and later published by a short-lived body called the Rock Writers’ Collective. It was also used by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood for a clothes shop on the King’s Road in premises that had begun life as Paradise Garage and would continue as Sex, Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die, Seditionaries and World’s End.

Berry was the great librettist of the first era of teenage music. He took the preoccupations of the blues and country music and gave them a rejuvenating twirl, introducing names, detail and incidental colour in a way that brought entire scenes to vivid life, painting pictures in the minds of those for whom Georgia and Louisiana were an ocean away.

Never did his words and music fuse more effectively than on Memphis, Tennessee, where the plaintive guitar and Latin rhythm underscored the sad, sweet story of a man far from home, trying to place a call to a girl who turns out to be the six-year-old daughter of his broken marriage. The portrait of Johnny B Goode, the country boy who extracted his guitar from a gunny sack in order to strum along with the rhythms of passing trains, is extended into Bye Bye Johnny, where the protagonist leaves Louisiana for the Golden West, his dreams of a career in motion pictures funded by a doting mother.

Berry’s gift reached its apogee in Promised Land, probably the finest song ever written about the American dream. A modern Odyssey, it describes a journey from Norfolk, Virginia to Hollywood by Greyhound bus, Midnight Flyer train and jet plane, giving details of family favours bestowed on the “po’ boy” en route (“They bought me a silk suit, put luggage in my hand”) and the wonder of in-flight meals (“Working on a T-bone steak a-la-carty”) before the magic moment arrives: “Swing low, chariot, come down easy / Taxi to the terminal zone / Cut your engines and cool your wings / And let me make it to the telephone.” When Elvis Presley recorded it at the Stax studio in Memphis in 1973, the former truck driver sounded like a man who had lived the song: “Tell the folks back home this is the promised land calling / And the po’ boy is on the line.”

Berry also demonstrated that the new music could be made with a sense of humour that did not compromise its credibility. He could empathise with the put-upon young man seeing the summer slip away in the monotony of a dead-end job – “Workin’ at the filling station, too many tasks / Wipe the windows, check the tyres / Check the oil, a dollar gas” – and with the young lovers fumbling their way to a session of 1950s-style heavy petting: “The night was young and the moon was gold / So we both decided to take a stroll / Can you imagine the way I felt / I couldn’t unfasten her safety belt.” With its adolescent epiphanies and insecurities, what was George Lucas’s American Graffiti, if not a two-hour Chuck Berry song?

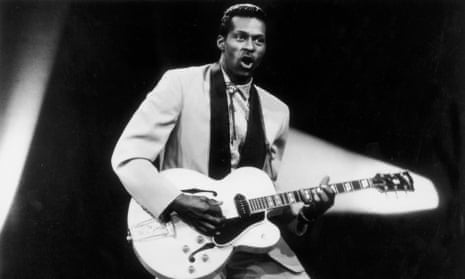

Although Berry was already coming to the end of his 20s when he recorded Maybellene, his very first hit, in 1955, he had the gift of sounding young – sometimes disturbingly so. When you were a teenager, it didn’t seem to matter that Berry was obviously 10 years or more older than the pubescent girls he celebrated; his unapologetic loucheness, and the fact that he played guitar like ringin’ a bell while sliding across the stage in his patented Duck Walk, took him right out of the category of grownups.

In 1962, at a time when he owned a nightclub and was investing in real estate, and just as his British disciples were about to spread his fame, he served an 18-month jail sentence for contravening the Mann Act, a US law penalising those guilty of the offence of taking an underage girl across a state line for immoral purposes. It seemed like a vicious piece of discrimination, as brutal as the persecution of Jerry Lee Lewis for doing what had come naturally in rural Louisiana (ie marrying his 13-year-old cousin). But then, in 1990, Berry paid more than $1m dollars to settle a collective lawsuit from a group of women who claimed that he had installed a video camera in the female restrooms at his restaurant, the Southern Air, in Wentzville, Missouri. As with Roman Polanski, the shadow lingered.

After that first prison term, he was never the same creative force. While he was inside, he wrote his last really memorable songs: No Particular Place to Go, Nadine, You Never Can Tell, Tulane and Promised Land. In the following years he gave many performances that were barely even perfunctory, he insisted on being paid in cash (a habit that eventually landed him in trouble with the tax authorities), he was evasive and enigmatic in his encounters with the media, and he never seemed more than superficially grateful for good fortune that came his way, whether the eventual No 1 hit with the egregious My Ding-a-Ling or a command performance at the White House in front of Jimmy Carter in 1979. But back when it was all new, he was the one who really laid it all out.

- This piece was amended on 19 March 2017 to correct the age of Marie in Memphis, Tennessee.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion