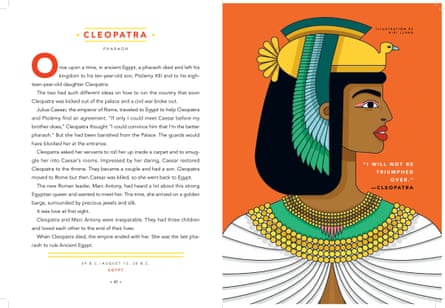

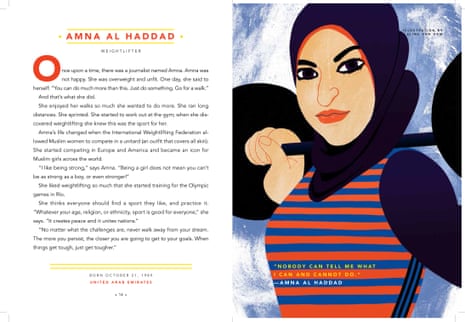

The book is called Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls, but reading a handful of its 100 stories about some of the most brilliant women in history at bedtime might not be a good idea. Featuring spies, pirates, astronauts, activists, scientists, writers, sports stars and more, many of the stories are so thrilling and uplifting your child’s heart may beat a little faster, her mind racing with possibilities. If she leaps out of bed to get to work, blame the authors.

Francesca Cavallo and Elena Favilli launched their crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter and IndieGogo, with the aim of raising $40,000 (£32,000) to create and print 1,000 copies. They ended up raising more than $1m, with the book becoming the most highly funded original book in the history of crowdfunding. The pair had moved to the US from Italy in 2011, and had formed their own children’s media company, Timbuktu Labs, and created an iPad magazine and several apps. Working in children’s media, says Cavallo, “we saw how children’s media and books were still packed with gender stereotypes, and we really wanted to create something that could break the rules, with a new type of female protagonist, and examples of strong women from the past and present who have done incredible things. We really wanted to show the true variety of fields, disciplines and jobs, just to show the full capabilities of women and to inspire young girls to believe they can try to do anything.”

In less than two weeks, their video advertising for the book has notched up 24m views on Facebook. It shows a mother and daughter removing books from a bookcase according to a range of criteria: is there a female character? Does she speak? Do they have aspirations, or are they just waiting for a prince? By the end there are few books left. Although it was described as an “experiment”, it wasn’t exactly – the bookcase wasn’t a randomly chosen one, but was set up to represent figures from studies into gender disparity. The data it referenced is alarming enough – 25% of 5,000 books studied had no female characters; across children’s media, less than 20% showed women with a job, compared to more than 80% of male characters.

This article includes content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

“It does something to you,” says Favilli. “When you never see someone making the headlines, or a protagonist in a book or a cartoon, it becomes more difficult to imagine yourself in a leading role or position.” At readings they have done, children of both genders are consistently surprised to learn that “women have done so many things”.

If you grew up reading the Pippi Longstocking books, or the Paper Bag Princess (published in 1980, it is still one of the most famous books to subvert the prince-and-princess format), you might be dismayed to hear that children’s books haven’t seen much progress. If you watched that video on Facebook, you might assume that children’s publishing appears to be in a state of crisis about gender. That’s not strictly true. A look at the website A Mighty Girl, a database of empowering children’s fiction, reveals nearly 3,000 books in which girls are the central characters (the British website Letterbox Library is another great resource). “There are a lot of them out there, but one of the biggest problems is that people don’t know where to find them,” says Carolyn Danckaert, who founded the site with her partner after struggling to find good books for their young nieces. She thinks representation of women and girls in books is getting better. “I think a lot of publishers and authors have become increasingly aware of it and are responding,” she says.

In 2011, Janice McCabe, associate professor of sociology at Dartmouth College, and her colleagues published a large study into children’s books. She looked at more than 5,600 books published in the US throughout the 20th century, and found a huge gender imbalance. Male characters were central in 57% of children’s books, while only 31% had female central characters. And males featured in the titles of 36.5% of books each year, but only 17.5% of titles referred to a female character. All this, she says, “contributes to a sense of unimportance among girls and a sense of privilege among boys. The inequalities we found don’t just exist in children’s books. Studies of other children’s media show these similar patterns – male-dominated characters in cartoons, video games, films, even in colouring books.”

Animal characters showed particular inequality in genders, with male animals central in more than 23% of books, compared to 7.5% containing female animals. And even where the animal’s gender was not explicit – often the author’s attempt to get away from gendering the character – McCabe pointed to research that showed mothers and fathers assumed the animal was male and assigned male pronouns to it. As a result, she says, the figures for gender disparity that came up in her research are “likely a conservative estimate of what children are exposed to, and one [reason for this] – and I even catch myself doing this – is that when you talk about animals in books, the default becomes male. It’s interesting that these patterns are hard to break. It’s not really a conscious decision. It’s implicit bias.” Another reason is that the books selected for her study were representative of what was published, but not necessarily representative of what might be found on an average child’s bookshelf. Children will often be given books by their parents and other older relatives who enjoyed them when they were little. “You can see that they are often getting a lot of books from the past,” she says – books that might reinforce older ideas of gender stereotypes.

Her sons are aged five and two, and she says that although there are many books with compelling central female characters, she has to put some effort into finding them: “They’re not the books you’re likely going to get if you just pick one at random.” Her boys are still at the age when they will happily read books about girls, but “my oldest is at the age when rules about gender become stricter as a developmental trend, so I’m curious to see whether this holds as he gets older,” she says.

The writer and illustrator Lauren Child, author of the Charlie and Lola series, among others, says she hears this idea all the time. “Very often, if you write a book that has a lead character that is a girl, publishers want you to slightly ‘girlify’ it, to make it look more like a girl’s book. [They think:] ‘Let’s not even try to sell it to boys.’” Over the last few years, there has been an explosion of pink-covered, glittery books.” Child started her Ruby Redfort series, about a daring 13-year-old undercover agent, in 2011. “I can’t help feeling that if I’d written Ruby as a boy character, they’d have better sales, because it does make a difference in the way it gets marketed.”

The decision to make her child detective a girl was a deliberate one. Her first book, Clarice Bean, That’s Me, was published in 1999, was the start of a series. Child made the protagonist a girl because “it was a case of writing about a world I understood – I had been a girl and was writing a bit about my memories. But then it became quite important to me to write from the point of view as a girl. I wanted to have someone who had a strong voice and a strong place, hopefully, in literature, who was a girl. I remember reading Pippi Longstocking, and it had nothing to do with her being a girl – but you saw a very strong, courageous, funny, clever person who happens to be a girl, and that meant a lot to me when I read it.”

With Ruby, “I wrote about a girl who is courageous and brave and clever,” Child says. “She’s an adventurer, an action hero, and it was important to me that she was a girl because girls are always the sidekick in films and books. I find it a little depressing that we have moved on so little with our thinking.”

Not everyone thinks there is a problem. Referring to the Rebel Girls’ bookshelf “experiment”, Kate Wilson, managing director of the children’s publishing house Nosy Crow, says: “I could have assembled a different bookshelf for that child, filled with brilliant books. Any bookseller or librarian worth their salt could put together a different bookshelf.” In the UK, more than 10,000 children’s books are published every year. “I think the challenge is how to find the books that are right for you. Libraries and bookshops have an incredibly important part to play in that, because we have incredibly knowledgable people who can guide you towards things. But there’s no lack of great books with girls as central characters.”

She admits the publishing world needs to make more effort when creating animal characters. “The default seems to be to assume that a crocodile, or a Gruffalo, or a mouse on a page is male.” She describes one of the books she published last year, Don’t Wake Up Tiger!, in which the tiger is female, as “really unusual, particularly for a predatory animal. A tiger is ostensibly the scary creature, and we made a deliberate choice about [her gender] … As an industry we have to think about pronouns and gender attributions for animal characters in younger books, but I think otherwise things have moved on, and a lot of the strongest stuff we see at the moment has a girl protagonist.” She points to The Mystery of the Clockwork Sparrow by Katherine Woodfine, a historical crime novel in which two girls solve a crime; Rooftoppers by Katherine Rundell (another mystery with a girl as a central character) and Attack of the Demon Dinner Ladies by Pamela Butchart, which has a wealth of female main characters.

In the five years of running A Mighty Girl, Danckaert has noticed trends in publishing. Early on there were lots of “independent princess” books, which were “pushing back against the princess stories that had dominated. The concept of the girl power book is not new. We have a classics section on our website and there are books there going back to the 1940s.” In the last couple of years, she says, there has been “a boom in picture-book biographies, and particularly books with a science theme. Books of those sorts have been very popular on our site.”

Wilson says parents are increasingly asking for diversity, and that booksellers report they explicitly ask for books that reflect feminism. The huge success of the Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls crowdfunding campaign, and the book itself (at the time of writing, it is number five on Amazon), points to this. There are similar books, including Kate Pankhurst’s bestselling Fantastically Great Women Who Changed the World, which was published in September and, for older children, Rad Women Worldwide.

McCabe says she found that improvements in gender parity in children’s books often followed waves of feminism. “The mid-century period was when there was the most unequal representation of girls and women, and female animals.” Where there were periods of noticeable feminist activism, the gap closed, she points out, so signs are good for contemporary children’s books. Great books featuring girls are out there, but it seems to be more a case of visibility – much like many of the real-life women chosen to inspire girls at bedtime.

Great books with female characters for the under-fours:

Wild by Emily Hughes, featuring a green-haired, huge-eyed, untameable heroine.

Interstellar Cinderella by Deborah Underwood and Meg Hunt: Cinders saves the prince with her mechanical aptitude and jets off for exploration instead of marriage.

For ages five to eight:

Nelly and the Quest for Captain Peabody by Roland Chambers, illustrated by Ella Okstad: A bold, resourceful girl sets out with her pet turtle to find her father.

Women in Science – 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World by Rachel Ignotofsky: Gorgeous illustrated account of rebelliously brilliant women.

For ages eight to 12:

The Wolf Wilder by Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Gelrev Ongbico: In Tsarist Russia, Feo and her mother return tame wolves to the wild. When her mother is arrested, Feo will need all her courage to free her.

The Secret of Nightingale Wood by Lucy Strange: When her father goes away, Harry fights tooth and nail to keep her mother out of the asylum.

For teenagers and young adults:

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas: When Starr sees her childhood friend shot dead by a police officer, her life is forever changed. Chosen by Imogen Russell Williams, Guardian children’s books critic

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion